SATURDAY AFTERNOON, MELBOURNE, Australia. It is 4.30pm local time and still the wee small hours back home. Bear with us as we briefly travel back in time, to 1956, the 1500m Olympic final, a field so competitive that the defending champion is eliminated in the heats.

Twelve men enter the arena, one leaves as an icon, his name subsequently carved onto marble at the stadium entrance.

Ronnie Delany believes it was his destiny to win that day but few others get to feel that way. Theirs is a life of sacrifice without the reward. “An Olympian is someone who tests themselves against the best in their sport, someone who takes risks – who is prepared to be less equipped for the life that follows their sporting career,” says Ben Fletcher, Irish judo’s medal hope.

“I’m 29. Most other 29-year-olds are set on a (nine-to-five) career and have probably earned more than me. Still, I’m more than happy to throw away the comfort of what life in the western world can offer you for the challenge of seeing how far I can go in this sport.”

To get an idea of the ‘risks’ involved, many of Ireland’s modern-day Olympians have lived one step removed from poverty at some stage of their career; surviving off grants that see them ‘scrimp and save’ and rent the ‘cheapest room in the city’ because it served their athletic needs. “If I didn’t do that, then I wouldn’t be true to my six-year-old self, the kid whose dream was so pure,” said Brendan Boyce, our world class race walker.

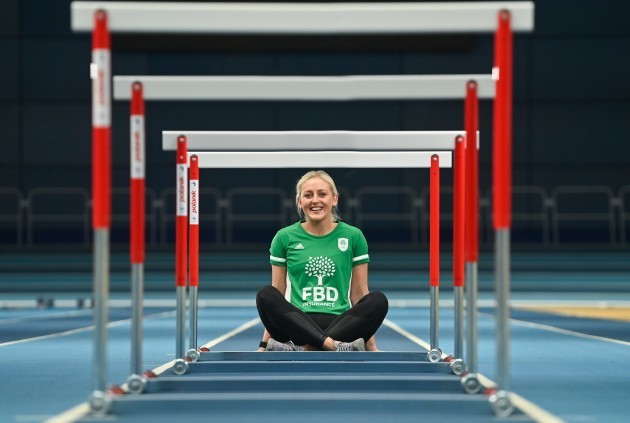

Boyce is quiet, uncomplicated, and really hungry to succeed in Tokyo. Fletcher has a different personality yet the same attitude, as does Sarah Lavin, the Limerick 100m hurdler, ranked ninth in Europe. Their names are well known within their sport’s familial circle yet on a national scale, their profile remains low. Tokyo could change that. “Forever,” Fletcher says, knowing the Delany story. “We could be remembered forever.”

- For more great storytelling and analysis from our award-winning journalists, join the club at The42 Membership today. Click here to find out more >

Deep down, it’s a prize every Irish athlete craves. “It could be over for me in a matter of minutes (in Tokyo),” says Fletcher, “and I guess it takes a specific type of person who is willing to give 15 years of their lives to do that, to run that risk.”

A judo bout lasts five minutes, so a first round loser won’t even get his 15 minutes of fame. But win and who knows where it could take Fletcher, potentially to a place in a nation’s hearts, where his name, like Delany’s, will also be carved into stone, outside an Olympic Stadium.

That’s why he does it, not for money, fame, even for glory. For Fletcher, Lavin, Boyce, for just about every one of Ireland’s Olympic team, it’s about something much deeper: their pride.

THE DREAMERS

In Sarah Lavin’s school, the girls and boys always used to race to the meadow at break. Whoever got there first claimed territory. Sarah was always the girls’ big hope. When she won, they all got to play in the favoured spot of the school grounds. That’s when she first figured out she was fast, a view confirmed when she won a Munster championship as a seven-year-old, despite giving away two years to her competitors.

That same summer, all the Lavins travelled to Tullamore for an All-Ireland. She won there too. “I fell in love with the sport,” she says.

For better, for worse, in injury and in health, she’s been wedded to it since. Lavin – a 100m hurdler – is 26; Fletcher 29. When they hear Boyce’s story of ‘being true to the six-year-old kid who dreamed of being the best athlete in the world,’ it resonates. “Every choice I make is like a conversation with a seven-year-old me,” says Lavin.

“The love I had for running then, the desire to be as fast as I could, that’s still there now. I’m so close to being an Olympian. It is going to be a busy two or three months to try and make it (to Tokyo). Everything I do now is based on the dream I had as a seven-year-old.”

Delany, our hero from ’56, knows where they are coming from. In an era when emigration was rife, he quit his cadetship in the Irish army and embarked on something that was then unknown – an athletics scholarship in the US. “Here I was, in a good, safe job, throwing it all away,” Delany recollects. “But it was something I had to do. You see I knew I was good and I don’t want to sound immodest but I felt I could become a great athlete.”

Fletcher doesn’t believe in destiny. But like Delaney in ‘56, he too is on a mission. Born into an Irish family in England, he decided, five years ago, to transfer allegiance from the UK to Ireland, having already obtained an Irish passport. His grandfather (John Joseph Keating) grew up in that era Delany talked about, forced to bring his family – including Fletcher’s mother, Alice-Mary, across from Bruff in Limerick.

“I don’t have the words to say this – but mum and all our Irish cousins, aunts, uncles, would just be so proud if I represented Ireland in the Olympics,” he says. “It would mean a massive amount to her. That’s what is driving this.”

As he speaks, his leg – in plaster after a recent injury in Israel – is resting. Ranked 12th in the world, he knows only the top 16 will make it to Tokyo. This is sporting purgatory, all this sitting around. After 15 years of training, missing out now would be torture.

Then again, hardship is what Olympians are used to.

‘I know you are getting married mate, but sorry I can’t go. I’ve judo.’

First it was 18th birthday parties; then twenty-firsts. As the years passed, and lives changed, weddings became the next events she missed out on. “You train twice, three-times a day, six days a week. It’s not a sacrifice, I hate that word. It’s a dream,” says Natayla Coyle, Ireland’s leading pentathlon competitor.

What is normal to them is extraordinary to anyone else. Take Fintan McCarthy, the rower who won a European championship gold last Sunday. An average week for him involves 13 training sessions, Monday to Sunday, 90-minute to two-hour sessions of low endurance rowing, mixed with weight sessions. Their reward for all this is half-a-day-off on a Sunday.

Then there are the ‘tough’ weeks; ‘15 sessions-a-week, when we do triple training sessions some days’. Friends of his have got their first homes, have settled into well-paid jobs. Athletes sacrifice all that.

“No, we don’t sacrifice anything,” counters Colin Jackson, twice a world champion hurdler and an Olympic silver medallist for Great Britain in 1988.

“I remember Daley Thompson, my sporting hero, talking to me about this as a young man. ‘What we do isn’t a sacrifice, Colin,’ he said. ‘Sacrifices are what miners do when they spend 14 hours underground so that they can put food on the table for their families. What we do is a choice’. And he’s so right. We could get a job; we don’t have to do this. We do it because we want it.”

Lavin concurs, saying: “When I was growing up, there were plenty of parties and nights out that went on without me …. but I wasn’t programmed that way to feel I was missing out. I can’t call them sacrifices. I’m 26 and I’m still getting away with running and jumping over things. This is everything I want.”

Whatever about missing a night out, she doesn’t even allow herself much of a night-in. “A good movie might come on a Sunday evening,” Lavin says, “but you just know you have to miss it; that your sleep and recovery is as important as training.” She charts everything, 12-and-a-half hours her 2021 record for unbroken sleep. Her all-time PB in the leaba is a 14-hour kip, the night before a European junior championship.

The last time she had a proper night out, alcohol lightening her mood, was in September 2019, a month of r&r in the hurdler’s diary. “I always feel I still need permission (to have a drink) even though I am 26.”

Fletcher feels the same way: “I don’t agree with the sacrifices thing. I can either do this and try and achieve my goal or not. When you start out, nobody has any idea how far they can get. You get to certain points of your career and re-assess. That is why it becomes an obsession where everything is tailored to being as good as you can.

“Like for example, on the social side of things, a friend was getting married not that long ago. I got the invite, rang him up and said, ‘sorry pal, it clashes with judo’. He was like, ‘but mate, it’s my wedding’. I still didn’t go. I couldn’t. Judo is the number one thing and everything else fits around that. That is why it is hard to do for a long amount of time. Most people can’t live that way for very long, from a mental perspective.”

ORDINARY LIVES, EXTRAORDINARY TALENTS

There may be decent support networks in place, maintenance grants, costs paid when they compete in international competitions, but an Olympian’s lifestyle isn’t luxurious. Many of them continue to live at home with their parents; Megan Fletcher – Ben’s sister, who also represents Ireland – even ended up training in the family-run garden centre during lockdown, a judo mat laid out between a cactus and a plant.

By the time November’s European championships came around, they went on a 22-hour round trip to Prague, driving there and back. That’s the reality athletes deal with in between Olympic Games. The lives they live, the money they earn, is strikingly similar – and sometimes worse – than their peers. Lavin lives with her sister, shares the cooking, watches Netflix, does all the things normal 26-year-olds do.

Except there is a difference. In June, they’ll leave these shores and these ordinary lives to travel across the world where an audience of 3.2 billion people will tune in to watch them perform.

After four years living like monks and in relative anonymity, they will embark on a rare sojourn into sporting showbiz. For some, stagefright will take over; for others, the spotlight won’t be the only thing that will shine. Knowing how to act under pressure will define their careers.

FEAR OR DESIRE? THE MENTALITY OF AN OLYMPIAN

No one athlete is the same. Some are driven by ego; others by fear. Lavin and Jackson are sprint hurdlers, standing either side of the Millennium, Jackson winning his second world championship in 1999, 11 years after he debuted in his first Olympic Games in Seoul.

He hears a story about an Irish athlete heading towards the 2019 European Championships, living with the fear she wouldn’t perform, that everything in her head was focused on Tokyo and qualification. “You are living with this idea you’ll feel like a bit of a failure,” the athlete said.

It’s a mentality he never had. “Fear is a really strong emotion,” he says. “I was lucky because I was able to do things most hurdlers couldn’t, in terms of some of my skills, the way I could make certain mistakes and get away with it.

“I was always very confident going into competition. The thing is, though, that there is a lot of judgment at the Olympics and some colleagues were worried about how they would be judged. Thankfully, I never really felt that. Instead in Seoul, when I saw the size of the crowds, I felt this wow moment.”

Fletcher felt differently in Rio. The opening ceremony; the security guards, the thousands of fans milling around, it was like nothing he’d ever experienced before. Having gone through all that once, the next time, he pledged to himself, he’d remind himself that it was still just a judo tournament.

For Lavin, there’s a sense of wonder. This will be her first Olympics. “I love the big day. I love it boiling down to the championship, looking around, seeing the best of the best there; knowing you are a part of that, that it is time for you to step up. I love that.”

She’s in the form of her life, breaking her personal best six times in six weeks this year. “I was ninth in Europe this year. It felt great. Only eight athletes on the continent are ranked higher. But I want more. I stood on the podium as a youth; stood on the podium as a junior. That’s what I work so hard every day for.”

Winning is subjective, not just measured by a medal but by testing yourself against the world’s elite, pushing yourself to achieve things you never knew you were capable of. “The mind is so powerful,” Lavin says, “and we don’t have a clue how to tap into it. We have so much still to learn. At the moment, I am so focused on marrying my hurdle technique with my speed. Let’s see where it takes me.”

The answer, she hopes, is Tokyo, where Fletcher is also aiming.

He is a longshot for a medal but is heading there with a nice attitude, knowing he can win, without being neurotic about the possibility of slipping up. “In judo, more so than most sports, higher seeds lose when no one expects them to; anybody can beat anybody.

“I’m not one to believe in destiny but I do believe an Olympian is someone who wants to get to the top and be challenged against the best people of their time to see where they fit in. And while you know it could be over in a couple of minutes, you also know you could be a champion and remembered forever.”

It’s a prize worth chasing.

* Sarah Lavin is part of a new initiative that encourages schools to get active and learn more about the upcoming Olympics. School teams will log their physical activity which will be converted to a distance which will help their team get to Tokyo.

** Colin Jackson is promoting the 2021 Wings for Life World Run

(see WingsForLifeWorldRun.com )