UNTIL HENRY SHEFFLIN’S record-breaking achievements of recent years, the debate about hurling’s greatest player invariably narrowed down to the claims of Cork’s Christy Ring and Limerick’s Mick Mackey.

This extract from Hell For Leather: A Journey Through Hurling in 100 Games looks at what made Mackey so special

****************

The Ahane Colossus

1936 MUNSTER FINAL (Thurles, 1 August)

Limerick 8–5 Tipperary 4–6

“What was it that Mick had? Something we all know in our hearts, but find difficult to articulate. His dynamism, the sheer force of his personality, his leadership, courage, spirit of abandonment. All these and something more. Someone described it last night as ‘the old Duchas’.”

- Fr Liam O’Kelly speaking at Mick Mackey’s funeral

MICK MACKEY’S INTER-COUNTY career began with him being called in from the crowd to tog out for Limerick in a league game against Kilkenny in November 1930 and ended with an appearance as a sub in a 1947 Munster championship game against Tipperary.

In the intervening years, he became hurling’s first superstar, celebrated as the game’s ‘laughing cavalier’, ‘the playboy of the southern world’. His favoured position was centre-forward and while he was a skilful ground hurler and adept overhead striker, it was his electrifying solo-runs, goal-scoring and devil-may-care persona that endeared him to the crowds.

He is credited by some chroniclers with inventing the solo-run. Others maintain his father John ‘Tyler’ Mackey, another one-off who was presented with a gift of £100 by the Gaels of Limerick on his retirement, pioneered the tactic during his 16-year inter-county career that ended in 1917.

Standing about five foot 11 inches and weighing 13 stone, by all accounts Mick Mackey possessed unusual natural strength to match an innate sporting talent that would have made him formidable in any code. He treated Gaelic football as a secondary entertainment, but on one of his rare appearances for the county footballers, he scored 2–5 off the Kerry legend Paddy ‘Bawn’ Brosnan in a 1945 Munster championship game.

For close to 15 years, Mackey was an ever-present for club, county and province. Apart from the league and championship fixtures with Limerick, there were near annual appearances in the Munster colours and a relentless schedule of games with his club, Ahane. Ranked as one of the greatest club teams, Ahane twice won seven-in-a-rows of Limerick titles – 1933–1939 and 1943–1949, and there was a football five-in-a-row (1935–1939).

There were also many tournament and challenge games for club and county and all the time Mackey was a marked man, taking more punishment than he dispensed, though he was able to look after himself. He had to be, to survive in the era of the third-man tackle, frontal charge, and routine first-time pulling on the ball – without regard for head, arm, leg or any other body part in the firing line.

There is very little visual footage of Mackey in his prime, so the most compelling evidence about his hurling style is the testimony of his team-mates and writers such as P.D. Mehigan and Padraig Puirséal who, between them, were able to compare and contrast players from the 1900′s through to the 1970′s.

Mackey’s club and county team-mate Jackie Power used to go at it ‘hammer and tongs’ with Mackey at county training and remembered him as a ‘beautiful ball player, both left and right, he was strong as a lion and of course he perfected the solo-run. If Mick Mackey was playing today, the rules would suit his style of play down to the ground.

‘He often showed his body, on say Tuesday after a game and he would be black and blue. It was a case of stop him at all costs … You will hear a lot of hurling critics confirming other players for their scientific play, but Mackey was something special – he had great physique as well as skill and mobility, and daring spirit.’

Another Limerick team-mate, Dr Dick Stokes, remembered that it was Mackey’s sheer physical presence that drove his genius. Stokes maintained that ‘nobody hurled like him.

“He was a very strong, well-built man … and could use it and could think as well as everything else. He was able to throw fellows out of his way in a very purposeful way. In other words, it was always where the ball was … it was always constructive … He was unique in that respect. He could go up the middle. He never had to go up the sideline or anything like that.”

Alluding to Mackey’s fondness for playing to the crowd and joshing opponents, Padraig Puirséal wrote that Mackey ‘was the laughing cavalier of the hurling fields, a man to whom every game, big or small, brought an equal amount of immense personal enjoyment and an intense sense of personal challenge’.

Like many others, Puirséal felt Mackey reached his peak in the 1936 Munster final when he laid waste to Tipperary in Thurles and ‘utterly dominated the scene [and] silenced even the faithful Tipperary fans with an amazing total of five goals and three points, although there were times when it seemed he was being chased by half the opposing 15’.

The performance of Mackey and Limerick is all the more impressive given that they weren’t long back from a tour of America where Mackey had picked up a knee injury. Limerick came up with the idea of bandaging up his good knee as a ruse against Tipp in the Munster final.

Limerick’s stateside itinerary had included two games against a New York selection. The first joust drew over 40,000 spectators to Yankee Stadium and American sports journalist Dan Parker, writing for the New York Daily Mirror, was impressed by our national pastime.

“Hurling combines the best features of baseball, a heavyweight elimination tournament, hockey, a battle royal, golf and football. It is no game for a fellow with a dash of lavender in his make-up. It takes a strong physique to stand up under an hour of hurling for the pace is swift as well as gruelling.

“It is little wonder that the Irish have no plagiarists in hurling. They invented the game and though they haven’t copyrighted it, no other race has attempted to play it. I supposed the explanation is that no other race is constituted temperamentally like the Irish.”

It’s a shame Dan Parker never got to see the ‘pure drop’ of championship hurling as personified by Mackey and Limerick during 1936 when Mackey, aged 25 and captain, was a force of nature conducting a team of many talents.

There were few if any weak links from the gifted Paddy Scanlon in goal through to the classy Jackie Power at corner-forward. The half-back line of Mick Cross, Paddy Clohessy and Garrett Howard was the sturdy heart of the team with Howard a veteran of the 1921 All-Ireland-winning team.

At midfield were the Ryan brothers – Mick and Timmy ‘Good Boy’, famed for his stamina and overhead striking. The forwards included Bob McConkey, who had captained the 1921 team, Mackey’s brother John – rated by some as the better stickman – and Paddy McMahon, a native of Kildimo in west Limerick, who had been ‘signed’ by Ahane. McMahon was known as ‘the man to rock the net’ which says it all about his goal-scoring touch.

The Munster final was over after 15 minutes when Limerick led 3–1 to 0–0, Mackey having scored two goals and McMahon the third. Tipp tried to rally, but it was showboat time for Limerick, and Mackey relished sewing it into his near neighbours. His third green flag was described by the Irish Press as ‘a peach of a goal’ after a team effort involving several passes.

It was 5–3 to 2–0 at half-time and in the second half ‘Mackey raced clean through for his fourth goal’ and for the fifth ‘crashed his way through a bunch of players to slap a pass from Cross to the net’.

The main photo on the sports pages of the Press two weeks after the Munster final showed hardy-looking gangs of Galway and Limerick supporters squaring up to each other with a garda standing between the two main protagonists.

Ructions erupted in the second half of the All-Ireland semi-final at Roscrea. Galway had led 2–3 to 0–7, but ‘Limerick exploded out of the blocks’ in the second half, scoring 2–2 in three and a half minutes to reach the ‘fairway to victory’.

The row started after Mackey made an ‘unstoppable burst, breaking through all opposition for a goal’ that made it 4–9 to 2–4. The Galway team then walked off the pitch in protest at the referee’s failure to take action after one of their men had been ‘badly hurt’, reported the Press.

The sense that Limerick were unstoppable was confirmed in the All-Ireland final where they emphatically reversed the 1935 defeat – wiping out Kilkenny by 5–6 to 1–5. ‘Youth and physique allied to vastly improved hurling skill triumphed in Croke Park in front of a record attendance,’ reported Pat’O in The Irish Times.

‘They are the first team to lay the American ghost – Tipperary, Kerry, Kilkenny, Galway, Mayo, Cavan, all have failed to hold their titles on return from American tours. Limerick seemed to have thrived on Dr Atlantic. That they should prove Kilkenny’s masters in pure ball playing art was a surprise to all the critics … In the open as well as the close, overhead as well as on the sod, the Munster men were superior.’

Mackey slalomed past four Kilkenny defenders for the final Limerick goal. It brought the curtain down on the perfect season for the Ahane man. Later in life, when asked about his own hurling style by Val Dorgan, Christy Ring’s biographer, Mackey said, ‘I suppose I was a cool class of customer. It was good crack … Maybe Ring didn’t get the same fun out of it.’

==============

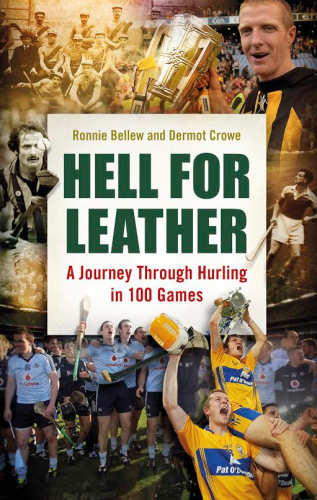

Hell for Leather: A Journey Through Hurling in 100 Games (Hachette Books Ireland) by Ronnie Bellew and Dermot Crowe is on sale now priced €24.99