THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from Ali: A Life.

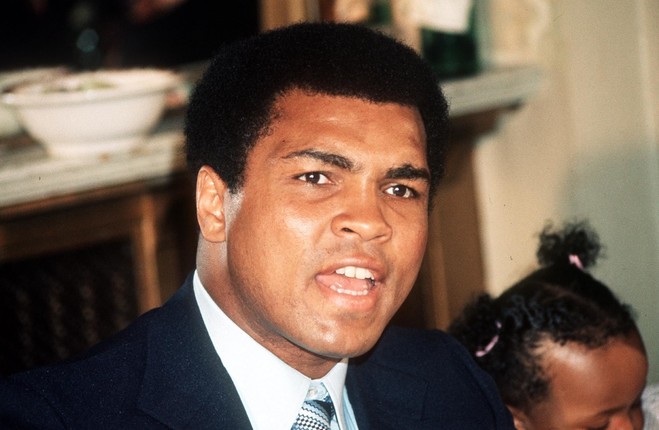

One day in November 1982, an elderly African man and a young boy rang the doorbell of Muhammad Ali’s big white house in Hancock Park.

Ali’s friend Larry Kolb answered.

“We are here,” the elderly man said, “because—before I die—I wish to introduce my grandson to the great Muhammad Ali.”

Ali told Kolb to let them in. The boy carried a Big Mac in a paper bag: a food offering for Ali. Muhammad hugged the little boy and performed a magic trick for him. He ate the Big Mac.

The elderly man said they had travelled all the way from Tanzania, going first to Chicago in search of Ali. They had been in Los Angeles three days.

“Today we found you,” he said, according to Kolb. “Tomorrow we can go home.” Ali fed them and then drove them in his Rolls-Royce to their low-budget airport hotel. He hugged them and kissed them and told them to go with God.

On the drive home, Ali told Kolb he believed that every person on Earth had an angel watching him all the time. He called it a Tallying Angel, because the angel made a mark in a book every time someone did something good or bad. “When we die,” Ali said, “if we’ve got more good marks than bad, we go to Paradise. If we’ve got more bad marks, we go to Hell.” Hell, he said, was like mashing your hand down in a frying pan and holding it there, flesh sizzling, for eternity.

“I’ve done a lot of bad things,” he told Kolb. “Gotta keep doing good now.

I wanna go to Paradise.”

Later the same month, Ali sat in the locker room of the Allen Park Youth Center in North Miami, a short drive from the spot where he had defeated Sonny Liston in 1964. He squeezed into a pair of boxing trunks and laced up his shoes, preparing for a workout, trying to get fit for a series of paid boxing exhibitions planned for the United Arab Emirates. The money raised during the trip would go to build a mosque in Chicago, he said.

A reporter asked when he would be back. He mumbled, words “clinging together as cobwebs of dust do,” as the journalist put it. “I’ll be gone six weeks,” he said, counting with his fingers. “I’ll be back November 10th,” he said.

“You mean December 10th, don’t you?” the reporter asked. “Yeah,” he said, lifting his eyes. “December 10th.”

“Then you’ll be away about three weeks, not six weeks.” “Yeah,” he said, slowly. “I’ll be away three weeks.”

It had been one year since Ali’s loss to Trevor Berbick. Since then, he had only joked about a comeback. “I will return . . . ,” he liked to say, pausing before adding: “To my home in Los Angeles.”

Now, he said, he was content to travel and raise money to promote his religion. He had come to the gym in North Miami to get in shape, to drop a few pounds, not with any interest in competing again, just so that he would look reasonably good when he boxed in exhibitions.

“My life just started at 40,” he said. “All the boxing I did was in training for this. I’m not here training for boxing. I’m going over to those countries for donations. When I get there, I’ll stop the whole city. You don’t hear nothin’ about Frazier, or Foreman, or Norton, or Holmes, or Cooney. But when I get to these cities, they’ll be three million people at the airport. They’ll be on the sides of the road going into the city.”

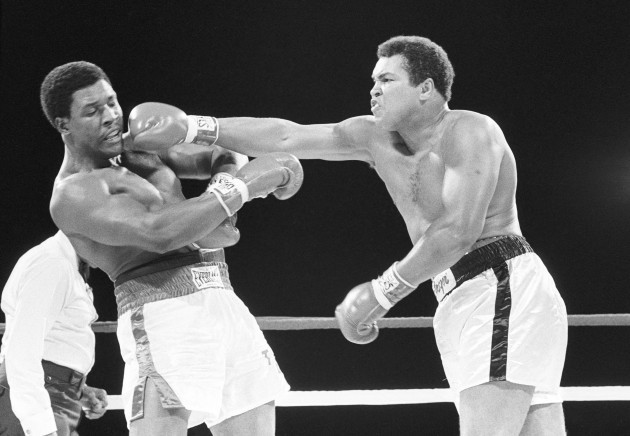

With that he went downstairs to the gym, climbed slowly up the small wooden steps and into the ring. The bell rang. Ali moved toward his sparring partner and punches pounded his headgear.

Two days before Ali’s interview at the gym in North Miami, a South Korean boxer named Duk Koo Kim had been knocked out and rendered comatose after a long, brutal fight with Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini. Soon after, Kim died of cerebral edema — swelling of the brain. The death prompted legislative committees in the United States to examine the safety of boxing. But, in the end, little changed. “What does the boxing profession think of the controversy?” asked US representative James J. Florio of New Jersey. “Well, the answer is: There is no boxing profession. It’s not a system, it’s a nonsystem, and it’s getting worse.”

In 1983, a pair of editorials in the Journal of the American Medical Association called for the abolition of boxing. In other sports, one editorial said, injury was an undesired byproduct. But “the principal purpose of a boxing match is for one opponent to render the other injured, defenceless, incapacitated, unconscious.”

Muhammad Ali, interviewed on national TV, was asked for a response to the editorial. He appeared tired and unfocused as he sat in front of the fireplace in his Los Angeles home. His voice came through soft and muddy. Asked if it was possible that he suffered brain damage from boxing, he replied faintly: “It’s possible.”

On April 11, 1983, Sports Illustrated published a special report on brain injuries in boxing, pointing out that deaths in the ring had long prompted calls for reform, but scant attention had been paid to the chronic brain injuries caused by thousands of blows taken over the course of a career. The magazine pointed to Ali as a prime example, saying that the former champ was not only slurring his words but also “acting depressed of late.”

To some observers, Ali seemed bored and emotionally detached. To amuse himself, he would take out his personal phone book and dial famous friends. But sometimes he would pause in the middle of the conversation, having forgotten to whom he was speaking. Sports Illustrated reported that “many observers” believed Ali was already punch-drunk.

The magazine asked Ali if he would agree to undergo a series of neurological tests, including a CAT (computerised axial tomography) scan, which was a relatively new tool for doctors at the time, one that was capable of revealing cerebral atrophy. Ali declined to undergo the test. But the magazine obtained scans of Ali’s brain taken at an exam at New York University Medical Center in July 1981 and showed them to medical experts. The radiologist’s report in 1981 had found Ali’s brain to be normal, but the doctors reviewing the scans at the behest of the magazine were more familiar with boxing-related brain injuries than most radiologists, and they disagreed with the earlier conclusion. They saw signs of significant brain atrophy — specifically, enlarged ventricles and a cavum septum pellucidum, a cave in the septum that shouldn’t be there.

“They read this as normal?” asked Dr. Ira Casson, a neurologist at the Long Island Jewish Medical Center. “I wouldn’t have read this as normal. I don’t see how you can say in a 39-year-old man that these ventricles aren’t too big. His third ventricle’s big. His lateral ventricles are big. He has a cavum septum pellucidum.”

The Mayo Clinic had spotted some of the same things but had deemed them unrelated to boxing. In an interview decades later, Dr. Casson strongly disagreed with that conclusion: “It was all consistent with brain damage from boxing,” he said.

Although he was finished as a fighter, Ali continued traveling extensively. He never tired of meeting new people and seeing new places. One night in Japan, as he was returning to his hotel room after dinner with his friend Larry Kolb, Ali stopped in front of his door and gazed down the long hallway. It was the custom at this hotel for guests to trade their shoes for slippers upon entering their rooms and to leave their shoes in the hall. Now, with most everyone asleep, there were shoes in front of every door. A mischievous look crossed Ali’s face. He nodded at Kolb. Without a word, the two men moved up and down the hall, rearranging the shoes. When they were done, they giggled and retreated to their rooms.

In May 1983, Ali was in Las Vegas, where Don King was paying him $1,200 “hang-around money” to schmooze with fans before a Larry Holmes fight at the Dunes. King knew Ali would engage with fans all day, even for a mere $1,200. He did it without compensation every time he stepped out of his home. And so the former champ signed autographs and performed magic tricks and ran into Dave Kindred, one of the reporters who’d been covering him since his earliest days as a professional fighter. “He was an old man at 41,” Kindred wrote.

Ali admitted he was worried about his condition. His friends and family were worried, too. He was drowsy all the time. He shuffled when he walked and murmured when he talked. His left thumb trembled. He drooled at times. He felt suddenly like an old man, and he wanted to know what was happening.

In October 1983, Ali returned to UCLA for more tests. This time, the signs of damage were impossible to ignore. A brain scan revealed an enlarged third ventricle in the brain, atrophy of the brain stem, and a pronounced cavum septum pellucidum.

Neuropsychological testing indicated that he had trouble learning new material. When he was treated with Sinemet, a drug for patients with Parkinson’s disease, he showed immediate improvement.

In interviews, Ali insisted there was nothing seriously wrong. “I’ve taken about 175,000 hard punches,” he said. “I think that would affect anybody some. But that don’t make me have brain damage.”

Even so, he said he wanted to find out why his body seemed to be betraying him. Ever since his fight against Joe Frazier in Manila, he said, he had felt damaged, and it was steadily getting worse.

In September 1984, Ali checked in to New York’s Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Centre, where he underwent several days of testing. He was seen by one of America’s leading neurologists, Dr. Stanley Fahn, who said Ali displayed a range of symptoms, including slow speech, stiffness in the neck, and slow facial movements.

“He was a little slow in his response to questions,” Dr. Fahn told the writer Thomas Hauser, “but there was no hard data to suggest that he was declining in intelligence.”

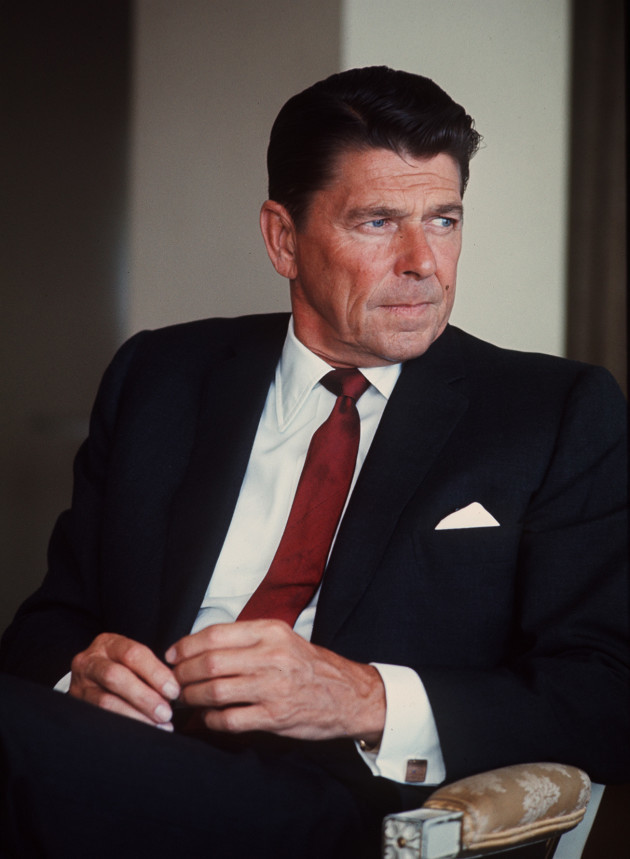

Ali was discharged after five days because he needed to travel to Germany. When he returned and was readmitted, news of his hospitalisation spread around the world. Floyd Patterson paid a visit, and Rev Jesse Jackson, who had recently given up a campaign for president, visited twice. Ali had given Jackson his endorsement in the Democratic primaries, but in the general election the former boxer threw his support to Republican candidate Ronald Reagan.

In 1970, as governor of California, Reagan had shot down Ali’s attempt to obtain a boxing license, saying, “Forget it. That draft-dodger will never fight in my state.”

When Larry Kolb reminded Ali of Reagan’s statement, Ali shot back: “At least he didn’t call me a nigger draft-dodger.”

Ali may have thought it was funny, but Jesse Jackson and others did not. “He’s not thinking very fast these days,” Jackson said after Ali’s endorsement of Reagan. “He’s a little punch drunk.”

Atlanta mayor Andrew Young was so upset he arranged a meeting with Ali, attempting in vain to change the former boxer’s mind on the endorsement.

Kolb, Ali’s friend and manager, stayed in a hospital room adjacent to Ali’s to keep him company and handle his phone calls. Veronica arrived soon after. Every day, Ali looked out the window of his seventh-floor hospital room and saw reporters and fans gathered on the sidewalk.

One day, Ali ventured outside to greet the crowd. “I saw so many people waiting and thinking I’m dying,” he told reporters, “so I got dressed and looking pretty to show you I’m not dying.” He raised his chin and shouted, “I’m still the greatest . . . of . . . allllll . . . tiiiiimmmmme!”

While conducting his examination, Dr. Fahn spoke to reporters at a press conference, saying tests virtually ruled out Parkinson’s disease as the cause of Ali’s symptoms. Instead, he said, Ali was likely suffering from Parkinson’s syndrome — an array of symptoms similar to those found in people with Parkinson’s disease.

Dr. Fahn said Ali would be treated with the drugs usually prescribed for Parkinson’s patients, Sinemet and Symmetrel. Ali’s condition, he added, was “very possibly” the result of blows to the head taken during his boxing career.

Only an autopsy could say for certain whether boxing had damaged Ali’s brain, according to Dr. Fahn. A British survey of more than 200 boxers published prior to Ali’s diagnosis found that about 10% of all former boxers suffered symptoms similar to Ali’s.

In neurology textbooks, Parkinson’s is listed as a degenerative disease of the brain. Nerve cells in the brain stem begin to die. As they die, the brain can’t produce enough dopa- mine, and the loss of dopamine leads to the shortened, unsteady stride; the slurred speech; the lost facial expression; and the trembling hands. These were the same symptoms that led to the description of the term punch drunk half a century prior and the same symptoms described by Sports Illustrated a year earlier in its special report on boxing and brain injury.

In an interview years later, Dr. Fahn said it was possible that Ali had been afflicted with these symptoms as far back as 1975, when he fought Joe Frazier in Manila, although the damage was certainly not caused by one fight. Ferdie Pacheco, having watched Ali fight through the years, expressed much the same opinion.

Ali’s boxing record also offered evidence to support Fahn’s theory. In the early years of his career, before his three-year ban from the sport, Ali had absorbed an average of 11.9 punches per round, according to an analysis by CompuBox. In his final 10 fights, he had been hit an average of 18.6 times per round. The numbers don’t prove that Ali suffered brain damage, but they strongly indicate that he was losing his speed and his reflexes, and that the cause may have been more than age.

“My assumption,” Fahn said, “is that his physical condition resulted from repeated blows to the head over time. One might argue that his Parkinson-ism could and should have been recognised earlier from the changes in his speech. That’s speculative. But had that been the case, it would have kept him out of his last few fights and saved him from later damage. It was bad enough to have some damage, but getting hit in the head those last few years might have made his injuries worse. Also, since Parkinsonism causes, among other things, slowness of movement, one can question whether the beating Muhammad took in his last few fights was because he was suffering from Parkinsonism and couldn’t move as quickly as before in the ring, and thus was more susceptible to being hit.”

The good news, Fahn said, was that Ali seemed as clever and intelligent as ever. His life was not threatened. And medication would ameliorate some of his symptoms.

Ali’s medicine kept his symptoms in check, but Ali didn’t always take his daily doses.

“I’m lazy and I forget,” he said. In truth, the pills made Ali so nauseated that he often preferred to endure his symptoms.

He continued travelling, continued boxing in exhibitions around the world, sometimes not sure where he was going one day to the next but trusting Herbert Muhammad to guide him. His ego, at least, was undiminished. “I’m more celebrated, have more fans, and I believe am more loved than all the superstars this nation has produced,” he said. “We have a saying, ‘Him whom Allah raises none can lower.’ I believe I have been raised by God.”

Even with his extensive travels, Ali spent more time at home now than ever, but he did not adjust easily to domesticity. The manly entourage had been his family most of his adult life. Now, he seemed unprepared for and perhaps uninterested in the life and work of parenthood.

Rather than settling down with Veronica and their two girls — Hana, age eight, and Laila, age six — Ali entertained an endless stream of guests at his home and took every invitation to travel as an opportunity to escape boredom.

Laila said she hated entering her father’s study because there were always so many people — “advisers, friends, fans, hangers-on.” After years of watching him on TV, she longed for her father’s company, and she did not wish to share him with the strangers surrounding him.

Ali was like a big kid, and his girls loved that. He took them to Bob’s Big Boy and let them order “a whole dinner of desserts.” He hid behind doors when they entered rooms and chased them around the house wearing scary masks. He swallowed all the kids’ vitamins so they wouldn’t have to. He tape-recorded conversations with his children, telling them they would be happy one day to have a record of their time together. He was enormous fun, but, as Laila told it, he did not provide the kind of warm, safe, and loving environment she craved.

“I never heard my parents fight,” Laila wrote in her memoir, “but their separate bedrooms said it all.”

In the memoir, she refers to her childhood home in Los Angeles as “the mansion” and “my father’s mansion.” With the exception of Thanksgiving, there were no family dinners. Maids and cooks kept the children clothed and fed. Laila was not impressed when celebrities such as Michael Jackson and John Travolta appeared in the living room. “I was drawn instead to another black family who lived down the street,” she wrote. “They ate together every night . . . The parents gave the kids rules and made sure they were obeyed. All this made me envious. I longed for such a family.”

Ali’s children from his first marriage saw their father two or three times a year. Jamillah, in a recent interview, said that she and her sisters, Rasheda and May May, got along nicely with their stepsisters, Hana and Laila. Ali did a good job of making sure Khalilah’s children got to know Veronica’s children. When Veronica and Muhammad were married, the children often spent summers together at the house in Los Angeles. Sharing her father with her stepsisters was not difficult, Jamillah said. “We had to share him, anyway,” she said. “We had to share him with the world.”

Ali’s illegitimate children enjoyed even less time with their father. Miya, Ali’s daughter with Patricia Harvell, said her father phoned her regularly and invited her to Los Angeles from time to time. Once, Miya said, when children at school were teasing her because they didn’t believe Ali was her father, Ali flew in, took her to school, and addressed an assembly of students, introducing himself as Miya’s father and speaking individually with some of those who had doubted his daughter’s claim. “That meant more to me than words can explain,” Miya said.

Veronica had to share Ali, too. Often, she remained in her room, feeling like a prisoner in her own home. She was never comfortable coming into the kitchen or living room unless she was fully dressed because she never knew who might be there. Veronica possessed a shyness that people mistook for frostiness.

“I became numb,” she said in an interview years later. “Yes, it was so much hurt. Too much hurt.”

Ali cheated on Veronica throughout their marriage. “He’d bring a woman right in front of you,” she recalled, “and later you’d find out he was fooling around with her.” Even when she learned that Ali maintained a steady relationship with Lonnie Williams, Veronica said she accepted it because she didn’t think her husband was really in love with the other woman.

Ali’s second wife, Khalilah (formerly known as Belinda), had also moved to Los Angeles in the late 1970s, which further complicated matters. In 1979, Khalilah had landed a part in The China Syndrome, which starred Jane Fonda and Jack Lemmon. But after that, her acting career foundered, and she burned through most of the money she had received in the divorce. By the 1980s, she was working as a housecleaner in the same Los Angeles neighborhood in which her ex-husband and his new family resided. She had also been reduced to selling her plasma for 90 dollars a week.

Lonnie arrived in Los Angeles in the mid-1980s. She was 15 years younger than Ali. She had first met the boxer in 1963, when her family had moved to a house on Verona Way in Louisville, across the street from the home Ali had purchased for his parents. Lonnie was a pigtailed first grader at the time. Her mother, Marguerite Williams, became one of Odessa Clay’s dearest friends. Through the years, Ali brought each of his wives to Louis- ville, and Sonji, Khalilah, and Veronica each dined at the Williams’s table. Lonnie watched them come and go.

In 1982, on a visit to Louisville, Ali had invited Lonnie to lunch. During the lunch, Lonnie became disturbed by Ali’s emotional and physical condition. “He was despondent,” she told Thomas Hauser. “It wasn’t the Muhammad I knew.” Soon, a plan was made and agreed upon by Veronica: Lonnie would move to Los Angeles to help care for Ali. In return, Ali would pay all her expenses, including her tuition for graduate school at UCLA.

Ali made no effort to hide his new relationship from his wife and children. In fact, Laila wrote, “He’d sometimes bring us along when he visited . . . her Westwood apartment . . . At the time, I didn’t know anything was wrong. It took me years to realise the inappropriateness of a married man introducing his kids to a special friend like Lonnie.”

In the summer of 1985, Veronica and Muhammad decided to divorce. Ali told his lawyers to ignore the prenuptial agreement, saying he didn’t want to be stingy. Some of Ali’s friends believed that Veronica was divorcing Ali because he was ill, but Veronica strongly denied it, saying she believed her husband’s condition was stable and he would enjoy a long and active life. She said she still loved Ali but left him because she’d been hurt too many times by his affairs with other women. “You cannot do that and then expect someone’s love,” she said.

On November 19, 1986, Ali married Lonnie before a small gathering of friends and family in Louisville. Lonnie’s parents were there, as were Cash, Odessa, and Rahaman.

Lonnie was 29. Ali was 44. He was starting over, not only in marriage but also in his body. All his life, his body had done everything he’d asked of it. He had been beautiful and strong almost beyond measure. As a young fighter, he had danced and dodged out of danger, stinging his opponents so quickly and sharply that he seemed never in peril.

After his three-year layoff from the sport, he had lost some of his speed but made up for it with cunning and power, making George Foreman his fool. In the final phase of his fighting career, he had lost his legs, lost his reflexes, lost his quick hands, lost everything but his guile and his willingness to suffer and endure.

Now, with his body abandoning him, with his voice a whisper, his feet shuffling, he would have to reinvent himself one more time.

Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig is published by Houghton Mifflin. More info here.